Graphics by Jade Khatib and Denise Lu

The new Cold War is a business opportunity, and Mexico looks better placed than almost any other country to seize it.

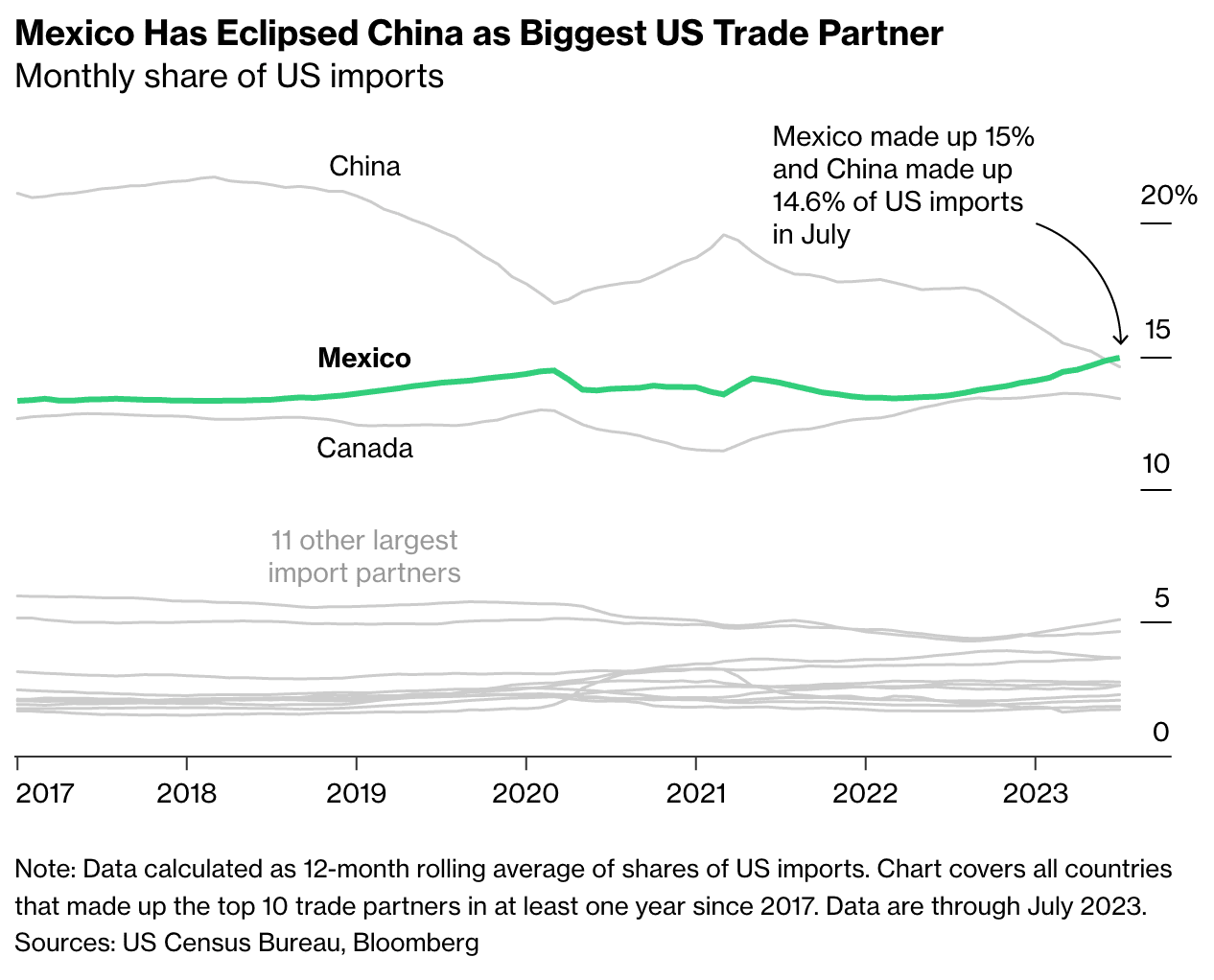

US-China tensions are rewiring global trade, as the US seeks to reduce supply-chain reliance on geopolitical rivals and also source imports from closer to home. Mexico appeals on both counts—which is one reason it’s just overtake China as the biggest supplier of goods to the giant customer next door.

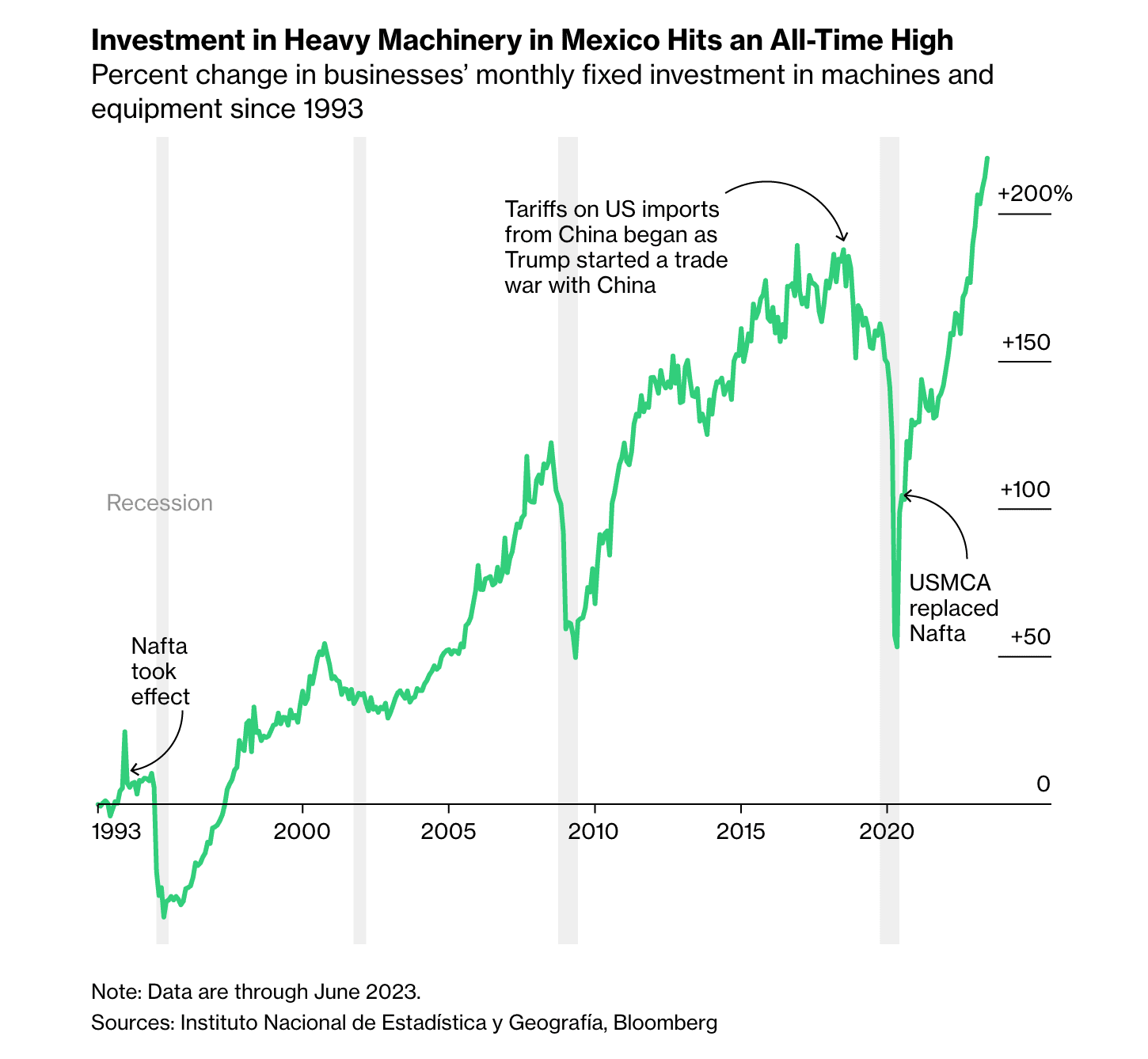

On top of resurgent exports, Mexico boasts the world’s strongest currency this year and one of the best-performing stock markets. Foreign direct investment is already up more than 40% in 2023, even before Tesla Inc. starts building a proposed $5 billion factory. Not since the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement in the 1990s has the country held the kind of allure for investors that it has right now.

Yet Mexico has a history of missing what could have been its moments. Over the past three decades, even a trade deal with the world’s biggest economy—which, just like today’s wave of so-called “nearshoring,” brought plenty of foreign investment—couldn’t pull Mexico out of rut.Since 1994, the year Nafta took effect, growth has averaged about 2% a year, well below par for developing economies, and nowhere near enough to lift millions of Mexicans out of poverty. Turkey, Malaysia and Poland are just three examples of nations that were poorer than Mexico at the start of this century and are now substantially richer.

And there are plenty of obstacles, old and new, that could cut the current boom short.

The government of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has repeatedly clashed with business interests as it seeks to bolster the state’s role in the economy. Mexican companies have been reluctant to borrow and make the investments that could help turn a growth spurt into something more enduring. And the country is up against fierce competition, from Vietnam and other nations, in the race to replace China as a supplier to the US.

What’s more, even the investments that Mexico is already getting are putting its infrastructure under growing strain, amid bottlenecks created by erratic power transmission, limited industrial space, and water scarcity.

Pedro Campa Eliopulos, a tech executive in the northern industrial hub of Monterrey, has a close-up view of Mexico’s potential for liftoff—and the limitations.

Two years ago, when Tesla was poised to open a factory in Texas, it was seeking a supplier to make the “brains” of its electric vehicles—the computers that connect to satellites, allowing autonomous driving—somewhere nearby, instead of shipping them all the way from China. Taiwan-based Quanta Computer Inc., Campa’s employer until recently, stepped up to meet the demand from a plant in Monterrey, the capital of Nuevo León state. “We started to outfit the building by August, and by December we were producing,” he recalls. Soon Tesla itself will be a neighbor, with construction of the Monterret Gigafactory due to start this year.

QuickTake: What 'Friend-Shoring' Means for the Future of Trade

Campa describes how the plant kept getting hit by power blackouts that took a chunk out of its productivity, because the city’s electrical grid struggles to keep up with its fast-growing industries. At such moments, he says, his thoughts on Mexico’s prospects turned gloomy. He wondered if “much of nearshoring will go elsewhere—because we don’t have the capacity to receive it.”

For all the pitfalls, there’s no doubt that parts of Mexico look like industrial boomtowns right now.

In Monterrey dust from the diggers is everywhere as new plants spring up. Warehouses are sold before the ceilings and the doors get put in. Industrial space has grown 30% since 2019, according to real estate adviser CBRE.

That’s partly because of the rush to provide components for Tesla. AGP Group makes windshields, China’s DSBJ makes electronics parts, Italy’s Brembo SpA makes brakes—and they’re all setting up or expanding factories.

All told, more than 30 companies have moved to Nuevo León since Tesla announced plans to build factories in Texas and Nuevo León, according to Iván Rivas Rodríguez, the state’s economy minister. “It was a request from Tesla to its suppliers, telling them ‘You have to come to North America,’” says Rivas, who sees his own job as making sure the deals close.

It’s not all about Tesla, though. Other carmakers including General Motors, Kia Motors and BMW have announced EV investments in Mexico since the start of 2021. Electronics and home appliance makers are expanding in the center of the country. Across the border from California, the aerospace and plastics industries are growing.

Industrial parks are filling up fast. Nationwide, vacancies fell to 2.1% last year, according to the Mexican Association of Private Industrial Parks. In Monterrey, getting a lease typically requires a 10-year commitment now. The association estimates that some three-quarters of renters are foreign companies. And a survey by Spanish bank BBVA found that one in five of the new arrivals are Chinese businesses—many of which are looking to sidestep US tariffs.

Industrial real-estate developer Corporación Inmobiliaria Vesta SAB raised almost $450 million in a US initial public offering in July that was the biggest by a Mexican company for more than a decade, and says it’s accelerating a $1.1billion pipeline of projects as nearshoring revs up demand. Prologis Property Mexico SA and its parent company are planning a $1.2 billion investment in warehouses and land.

Local landowners are among the big winners, too. “We’ve spent fifteen years saying, ‘We’re here, we’re here’—and then, boom!” says José María Garza De Silva, the third generation in his family at the helm of developer Grupo GP, whose early projects included housing developments and the city’s first shopping mall. The firm is a stakeholder in Monterrey’s biggest industrial park.

Still, Nuevo León’s natural resources might impose one set of limits on growth. A drought last year left reservoirs almost empty and thousands of residents without water. Local industry had to accept a smaller share of the state’s supplies, and the government is racing to build a new aqueduct to bring water to Monterrey.

Then there’s the question of whether domestic investment will pick up—which could help spread the benefits of the nearshoring boom more widely, and shift the economy onto a faster growth track. Absent that, some economists say Mexico will just end up importing more components to be assembled for export, with little value added locally.

Northern Mexican lender Banco Base SA has seen its loan book expand by some 75% over the past five years. That’s partly thanks to the renewed interest in exporting to the US, says Gabriela Siller, the bank’s director of economic analysis. But she’s concerned that Mexico isn’t making the most of this latest surge in investment.

“Nearshoring is an opportunity in Mexico, one that we’re not taking full advantage of,” says Siller. For reasons that include high interest rates and an entrenched informal economy, smaller businesses haven’t been able to use credit to expand, she says. “Many companies don’t want to take risks—the local ones more than the foreign ones.” And what investment there is tends to be concentrated in a handful of places, like Nuevo León.

That’s essentially what happened under Nafta too—and it’s the outcome López Obrador says he’s determined to prevent this time around.

The popular president, known as AMLO, is entering his final year in office and wants to leave his Morena party well-placed to hold onto power in elections next summer.

“We’re seeking to make growth in Mexico more horizontal,” AMLO—who hails from the relatively poor southern state of Tabasco— told reporters in April. He’s repeatedly pointed to the water shortage in places like Nuevo León as the kind of problem that arises when growth in the economy, and consequently the population, is lopsided.

López Obrador has earned a reputation for being anti-business. He’s tried to curtail the role of foreign firms in México's energy markets and earlier this year dispatched troops to renationalize a privately run railway line, before reaching an accord with its billionaire owner. On the other hand, the president was actively engaged in talks with Elon Musk about the Tesla investment, and says he welcomes job-creating foreign companies—he just would like to see them spread more evenly across the country.

So far, the leading contenders in next year’s presidential election say they’ll continue pushing to develop the south. Claudia Sheinbaum, who is AMLO’s protégée, has promised she’d see through many of his plans. Xóchitl Gálvez, a businesswoman and senator who’s the main opposition candidate, says she’ll seek to channel more investment into renewable energy, and better training for women to expand the country’s technical workforce.

Mexico made its reputation in world manufacturing with what are called maquilas—factories that sprung up as early as the 1960s, mostly along the US border. It was a profitable model of assembly-line production, employing low-wage labor. Under Nafta, exports got an additional boost, accelerating the growth of northern cities like Monterrey. But the trade deal also enabled a surge in imports of corn and other US-grown foods that made small-scale farming less viable—emptying out the Mexican countryside, and entrenching the wealth gap between north and south.

López Obrador keeps a notoriously tight grip on the public purse, but he’s made an exception for public investments aimed at leveling up the south. Projects underway include a rail link between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific, which goes by the grand name of Interoceanic Corridor. Officials envisage the route will be lined with industrial parks and say it could eventually rival the Panama Canal.

The problem, from an investor point of view, is that all these locations are simply further from the US. When Mauricio Garza, the director of Nuevo León’s biggest industrial park, is pitching customers, he never forgets to mention that you can drive to a border-crossing in under three hours without hitting a single red light.

Ultimately, Mexico’s appeal to global businesses rests on “its geography and its free trade agreement” with the US, says Gerardo Esquivel, a former deputy chief of the country’s central bank. “The reason they turn and look at Mexico, and that Mexico is attractive, is that it’s already integrated into the United States,” he says. That’s going to bring more investment flows “even if Mexico doesn’t do anything.”

Overall, Esquivel is upbeat about the boost that Mexico’s economy will get from nearshoring, citing estimates that it could end up adding as much as 0.7 percentage point of GDP each year. “It seems little, but it’s not, considering that we grow 2% per year,’’ he says. “Going up to 2.7% or 3% a year would be great.”

Link to Original Source - Bloomberg